The ILRS – Implications of the Joint Russian – Chinese Lunar Base

With the rest of the world distracted by a still persistent Covid pandemic, China and Russia today quietly announced what could be the largest international space cooperation project for both Nations.

According to the statement released by the Chinese National Space Administration:

On March 9, Zhang Kejian, the administrator of the China National Space Administration (CNSA), and Mr. Rogozin, the General Manager of the State Space Corporation “Roscosmos” (ROSCOSMOS), signed the Memorandum of Understanding between the Government of the People’s Republic of China and the Government of the Russian Federation Regarding Cooperation for the Construction of the International Lunar Research Station (also known as the ILRS). CNSA and ROSCOSMOS will adhere to the principle of “co consultation, joint construction, and shared benefits”, they are to facilitate extensive cooperation in the ILRS, which is to be open to all interested countries and international partners, and designed to strengthen scientific research exchanges, and promote humanity’s exploration and use of outer space for peaceful purpose.

The ILRS is a comprehensive scientific experiment base with the capability of long-term autonomous operation, built on the lunar surface and/or on the lunar orbit that will carry out multi-disciplinary and multi-objective scientific research activities such as the lunar exploration and utilization, lunar-based observation, basic scientific experiment and technical verification.

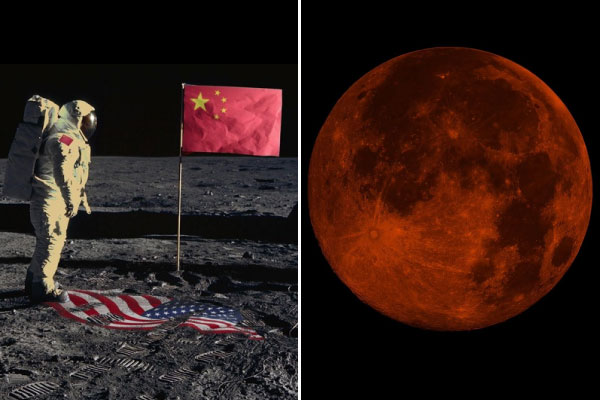

This announcement is significant because it signals the rise and maturity of China’s human spaceflight program and the concomitant loss of US preeminence and leadership in the sphere of international space cooperation.

These two fundamental developments will be the subject of this analysis.